Charting New Territory

Education Cannot Wait policy brief on foundation engagement outlines new opportunities to fund education in emergencies

By Johannes Kiess, Innovative Finance Specialist, Education Cannot Wait

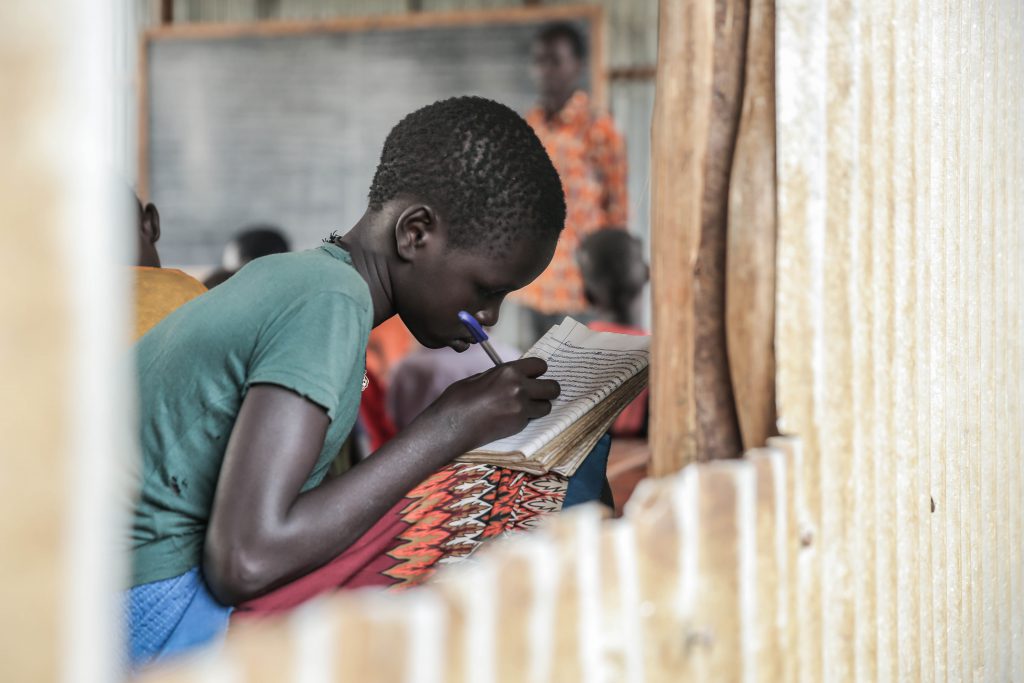

To fill the estimated US$8.5 billion annual gap for education in emergencies that has left millions of children behind, we need to accelerate our work and engagement with a wider range of partners. A key group of partners that possess vast potential, resources and know-how are found in the foundations space.

Education Cannot Wait has engaged with foundations since its inception. Dubai Cares, the foundations’ representative on our governance structures contributed US$6.8 million to ECW so far and was a major force in establishing the Fund. Dubai Cares also is one of the main private funders of education in emergencies.

“The establishment of Education Cannot Wait as a new global fund for education in emergencies allows foundations like us to support a mechanism that enables improved delivery of education to children and young people displaced by conflicts, epidemics and natural disasters through a coordinated and collaborative effort that minimizes transaction costs and maximizes impact,” said Dubai Cares CEO Tariq Al Gurg.

INSERTING EDUCATION IN EMERGENCIES INTO FOUNDATION GIVING

Our new policy brief “Foundations’ Engagement in Education in Emergencies and Protracted Crises” outlines that education in emergencies is becoming a priority for an increasing number of foundations. It’s an evolving space, but our analysis indicates a good potential for growth, strengthened coordination and mutually beneficial partnerships.

This isn’t necessarily news. The International Education Funders Group has hosted a group on education in emergencies for some years. This group took significant steps towards a more purposeful collaboration in 2018, and will be essential in any future planning.

We are also seeing a substantial increase in engagement from foundations. In 2017, the MacArthur Foundation awarded a US$100 million grant to Sesame Workshop and the International Rescue Committee (IRC) to educate young children displaced by conflict and persecution in the Middle East. In 2018, the LEGO Foundation awarded US$100 million to Sesame Workshop to bring the power of learning through play to children affected by the Rohingya and Syrian refugee crises.

In our policy brief – prepared with substantive inputs and data from members of the Education in Emergencies subgroup of the International Education Funders Group – we explore strategies to expand and strengthen our engagement with foundations for delivering quality education in emergencies.

KEY FINDINGS

- Education in emergencies is an important theme for several major foundations but not the only focus of their work. We are also witnessing new foundations entering the education in emergencies sector. This increasing engagement may be just the push needed to grow the pool of resources invested on education in emergencies beyond what traditional donors are giving. This engagement is expected to grow modestly with established funders and may increase with some large entrants from foundations previously not involved in the space.

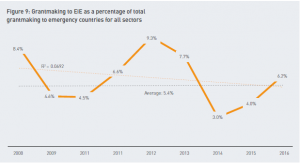

- Overall, foundation grantmaking to education in emergencies increased slightly between 2008 and 2016, the years for which data was available. Total contributions are estimated to be US$294.5 million over the past 9 years.

- About 5.4 per cent of all foundation funding to countries in emergencies went to education. This is above the global target of 4 per cent and above the actual proportion of 3.9 per cent of education funding as a share of humanitarian aid in 2017.

- Foundations gave on average 39 per cent of funding directly to local recipients and not through international organizations. This exceeds the 25 per cent target for humanitarian aid under the Grand Bargain commitment.

- Compared to official donors, foundations granted relatively more funds to secondary and early childhood education. Other priorities included ‘child educational development’ for children of all ages to foster social, emotional and intellectual growth, educational services, and equal-opportunity education.

- Foundations’ giving modalities are in line with recent developments in humanitarian finance to provide less earmarked funding, invest in data and evidence-driven programme management, and support broader systems reform and collaboration.

NEXT STEPS

These findings lead to a number of conclusions and recommendations for continued engagement and partnership with the foundations space.

First, while foundations already provide a significant financial contribution to overall humanitarian aid across education levels and for important priorities such as gender equality and equity, the enormous need to mobilize US$8.5 billion annually for education in emergencies requires foundations to rethink the scale and speed of their giving.

Second, foundations increasingly see funding as just one and not the only tool in their toolbox. They sometimes have deep roots in a country that go back well before a crisis started. If the education in emergencies community reaches out to foundations narrowly as just another source of funding, then it is unlikely to engage the foundations to their full potential. Taking this to heart, the education in emergencies community should engage with foundations in a way that shares and builds knowledge, networks and systemic capacity.

Third, closer collaboration, cooperation, and co-financing with other humanitarian and development actors – both non-profit organizations and UN agencies – may lead the way forward to strengthen the role of foundations in contributing to education in emergencies. Engagement in the multilateral funding system can help influence the global agenda.

Fourth, in order to operationalize coordinated financing on the ground, all education in emergency actors should develop and/or review their operating procedures and frameworks. This would enable public-private partnerships between foundations, governments, and multilateral organizations including global funds.

Fifth, going local is key for foundations. Foundations tend to work more directly with local actors than government and multilateral donors, according to the policy brief. This offers a clear value-add to potential partnerships. Foundations could help the wider education in emergencies community to better implement the localization agenda.

Sixth, foundations are a crucial voice in advocating for education in emergencies. They can play an important role in joint advocacy, engaging private sector champions, and lifting the profile of education in emergencies on the global agenda.

Finally, foundations have implemented education innovations – such as socio-emotional learning, development of soft-skills, learning through play, empathy, leadership skills, teamwork, conscientiousness, and creativity – supporting a holistic approach to children’s well-being. These are crucial for addressing some of the challenges faced by children living in crises.

By working more closely with official donors, foundations could share their knowledge, help scale up what works and ensure these programs are available to a much larger number of learners in emergency situations by integrating them into the larger programmes of official donors.

Taken from a 50,000-foot perspective, investing in education in emergencies offers plenty of opportunity for foundations to have real impact. As we step up engagement and convene dialogue and partnership between foundations and key education-in-emergency actors, it’s clear that there is a tremendous amount of growth potential. Only through strengthened collaboration and joining forces towards collective outcomes will we, as a sector, be able to meet the full scope of needs, and ensure every child, everywhere – even the ones most at risk that are living in war zones, conflict and crisis – has the hope, opportunity and protection of a quality education.