How Can We Capture the Impact of Crises on Out-of-School Children Estimates?

Read original from World Education Blog

By Manos Antoninis, Director, GEM Report; Silvia Montoya, Director UNESCO Institute for Statistics; and Christian Stoff, Chief, Monitoring, Evaluation and Global Reporting, Education Cannot Wait

In 2022, the UIS and the GEM Report proposed a major improvement in the way out-of-school rates and populations are estimated, making efficient use of different sources of information. Yet, the model has a weakness: when crisis strikes, estimates cannot be updated without new information. Sometimes such new information is collected. For instance, UNICEF carried out a household survey in Afghanistan in 2022/23 shortly after the new regime banned girls from attending school. This information enabled an updated estimate of the global out-of-school population, showing that it had increased to 250 million. Yet, this was an exception. In most cases, monitoring efforts break down in crisis contexts. Lack of security and urgent humanitarian priorities do not allow the usual data collection processes to continue. How can we make sure that children in these countries are counted in our global reporting?

At the UNESCO Conference on Education Data and Statistics last month, a session was dedicated to this issue: how to improve official education statistics and SDG 4 reporting to take into account crisis-affected populations. Two approaches were discussed.

First, a bottom-up and systematic approach would try to improve the annual UIS survey administered to governments so that it captures the impact of crises. Governments need guidance on how to document whether their education data collection is comprehensive or excludes particular regions and populations. Stronger collaboration among government institutions but also between government and humanitarian agencies would be called upon. In its decision, the Conference has requested the Technical Cooperation Group on SDG 4 indicators (to be renamed Education Data and Statistics Commission) to focus efforts on developing protocols and standards to capture the impact of emergencies and crises on affected populations. This sustainable approach will nevertheless require considerable efforts until government systems can adopt such protocols.

Second, a top-down and ad hoc approach would try to provide a short-term solution. It would focus on using documentation from humanitarian agencies to suggest by how much high-level estimates of flagship indicators such as out-of-school rates and populations would need to be adjusted to reflect the situation on the ground. Such adjustments would focus on the crises with the potentially strongest impact. How could that work in practice?

What do we know about five large humanitarian crises?

The International Rescue Committee has been publishing a list of the gravest humanitarian crises. In its most recent watchlist, the top five crises were Sudan, Palestine, South Sudan, Burkina Faso and Myanmar.

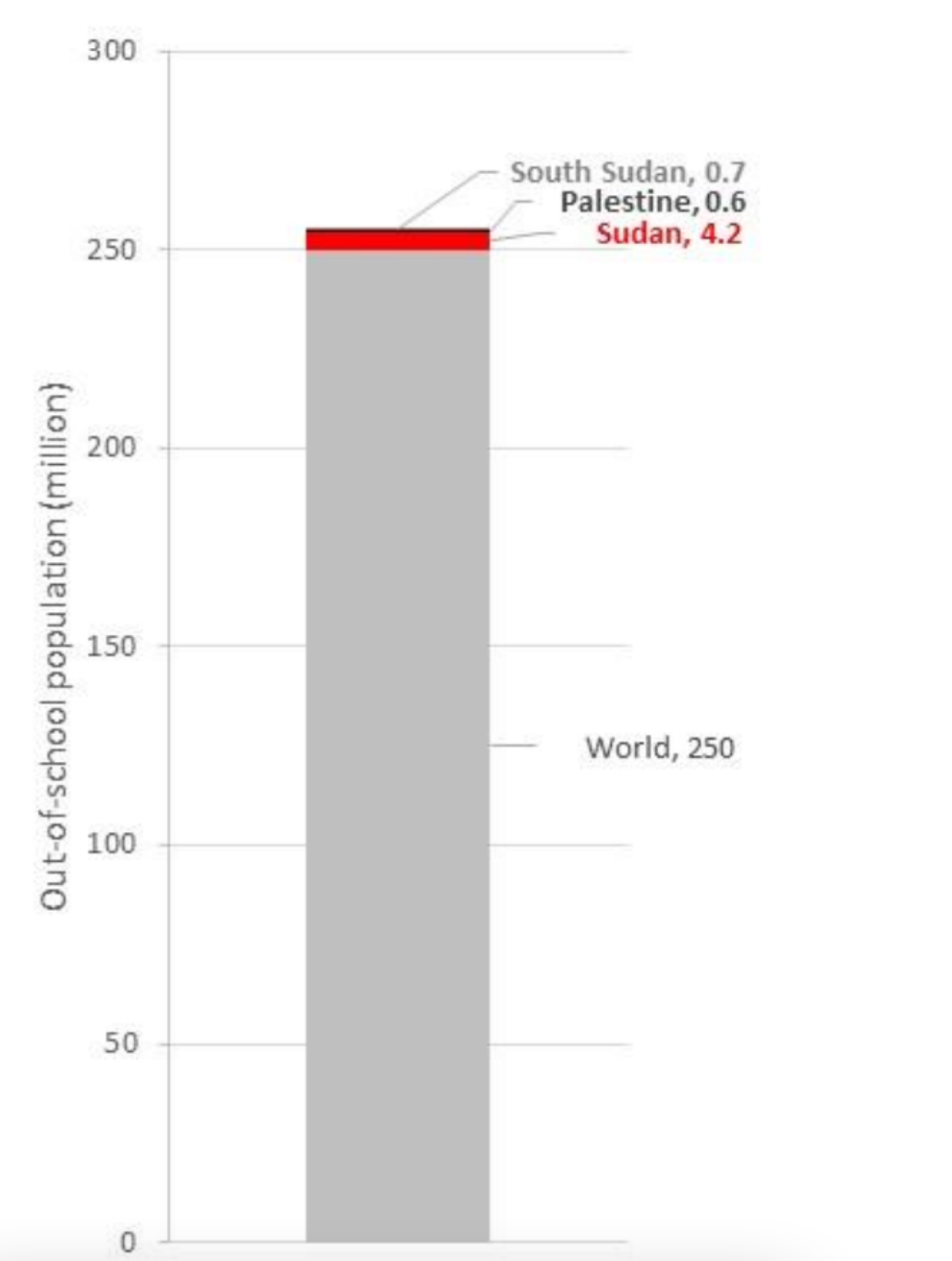

The largest displacement crisis in the world is in Sudan since civil conflict erupted in April 2023. More than 8 million people, about 15% of the population, have either been internally displaced or fled to neighbouring countries. According to the UIS/GEM Report model, there were 5.4 million, or 41% of children, adolescents and youth out of school in 2022, prior to the conflict. The GEM Report has confirmed this estimate was accurate following a recent analysis of a 2022 nationally representative household survey.

Civil conflict affected mostly the regions of Darfur, Kordofan and Khartoum. Of their respective school age populations, about 60% in Darfur and Kordofan and 18% in Khartoum were out of school in 2022. Assuming that no children went to school in the latter two thirds of 2023 in these three regions, 4.2 million would need to be added to the out-of-school population, bringing the total to 9.6 million. A widely circulating estimate that 19 million children are out-of-school appears exaggerated, considering that the school age population is about 13.3 million. It appears that some schools opened in Darfur in January, but at the same time other provinces are being dragged into the conflict.

In Palestine, all the estimated 0.55 million children aged 6-17 years in Gaza have been out-of-school since October 2023 and would need to be added to the global estimate. By late January 2024, it is estimated that 4,500 students have been killed and 9,100 injured. It is also reported that 76% of schools have been damaged. Even damaged schools are still used as shelters: more than half of school buildings are used for this purpose. Another 20% have been used for military operations.

South Sudan has suffered from a seemingly endless spiral of conflict and vulnerability to natural disasters. There are no easily accessible data for triangulation. The UIS/GEM Report out-of-school model estimated that there were 2.1 million children, adolescents and youth out of school n 2022. An estimate by the education cluster in December 2023 raised that estimate to 2.8 million. If verified, an additional 0.7 million children would need to be added to the global estimate.

In Burkina Faso, a crisis of insecurity due to continued attacks has been spreading to almost the entire country although 5 of the 13 administrative regions are disproportionately affected: Boucle du Mouhoun, Centre-Nord, Est, Nord and Sahel. The UIS/GEM Report out-of-school model estimated that there were 2.9 million children, adolescents and youth out of school in 2022, of which the five most heavily affected regions accounted for 1.5 million. Data from two surveys in 2019 and 2022 were used so the estimate is up to date, although it is hard to know how representative enumeration was in the affected areas.

An estimate by the education ministry in May 2023, with the support of the education cluster, found that more than 5,000 primary and secondary schools were forced to close in these regions, with almost 900,000 students losing access to education. Most likely this estimate overlaps with the existing higher estimates of the out-of-school population; it might be therefore safer to assume that no further upward adjustment is needed for Burkina Faso.

In Myanmar, it is more difficult to assess the situation. The last available official data are from 2018. The model projects that the improvement observed around 2015, when the total number of out of children, adolescents and youth was reliably estimated at around 2.9 million, would have continued, leading to an estimate of just 1.2 million out of school in 2022, but this is less reliable. The latest education factsheet published by UNCEF suggested that 3.7 million lacked ‘access to learning’, which is not the same as saying this population is out of school. It is unlikely that the out-of-school population would have increased by so much. In other words, it is not possible to make an informed suggestion.

In brief, evidence from three out of five major crises for which reasonably reliable and comparable information is available, suggests that the out-of-school population may be underestimated by 5.5 million.

Global out-of-school population adjusted by evidence from three large humanitarian crises

A way forward

Each crisis is different, in terms of characteristics such as intensity, spread and duration, but also in terms of data availability. Education clusters, which are mandated to coordinate humanitarian response in areas where the state may be absent, party to the conflict or not have the resources to identify needs and provide education services, are tasked with estimating the number of People in Need (PiN) of education.

It is important to remember that this is a different definition to being out of school. Clusters, after all, are assessing education needs for purposes other than global reporting. The result is that it is hard to combine and integrate their findings in official statistical reports. But more can be done to cross-check and take into account the data they provide when they can be triangulated with other sources.

There will always be a margin of error when it comes to reporting on education in crisis-affected situations. But the more we know, the less speculation there will be. And, as discussed a few days ago in a webinar organized by the Education Research in Conflict and Protracted Crisis (ERICC) Consortium and the Interagency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE), the more that an approach can be agreed upon by all parties, the easier it will be to ensure the publication of education statistics that reflect the situation of crisis-affected children and can inform policies and programmes.

Building on the UNESCO Conference on Education Data and Statistics, and under the framework of the Education Data and Statistics Commission, the next steps would involve the following:

- A task force that would propose by the end of this year a process on how to take supplementary information into account for estimating a margin of error in out-of-school population calculations, for a limited number of the most severe humanitarian crises.

- Based on these recommendations, introduce an annual process that will make these margin-of-error estimates.