Education Cannot Wait Interviews Professor Mohammed Belhocine, Commissioner for Education, Science, Technology and Innovation within the African Union

Professor Mohammed Belhocine is an Algerian national. Former Head of the Department of Internal Medicine, he held various positions in Algeria, at the Faculty of Medicine and the Ministry of Health, before joining the international civil service in 1997. Former Director of the Division of Non-Communicable Diseases at the WHO Regional Office for Africa (in Harare, then in Brazzaville), he was also WHO Representative in Nigeria and Tanzania. He ended his career as UN System Coordinator and UNDP Resident Representative in Tunisia from 2009 to 2013. From June 2015 to February 2016, at the request of the WHO Regional Director, he returned to duty as WHO Representative in Guinea, playing an active role in providing technical support and expertise to the country's response to the Ebola epidemic. In October 2021, supported by his country, he was elected to the position of Commissioner for Education, Science, Technology and Innovation within the African Union. Professor Belhocine is the father of three children and has six grandchildren.

ECW: 2024 is the Africa Year of Education. How can African Union Member States work with donors, civil society partners and multilateral organizations to transform and accelerate the delivery of education for girls and boys impacted by armed conflicts, forced displacement and climate-induced disasters in Africa?

Professor Mohammed Belhocine: The AU Theme of the Year 2024 is dedicated to Education, and it presents a crucial opportunity for African Union Member States to collaborate with various stakeholders to enhance education delivery for children affected by conflicts, displacement and climate disasters.

Leveraging existing frameworks like the Continental Education Strategy for Africa (CESA 16-25), countries can embark on policy alignment, ensuring the alignment of national education policies, prioritizing inclusive and quality education for all, particularly in crisis-affected areas.

In addition, AU Member States can embark on work with civil society partners, multilateral organizations such as UNICEF, UNESCO, WFP, Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and Education Cannot Wait, and multilateral or bilateral funding partners, to mobilize resources for education programs in conflict zones and areas affected by displacement and climate disasters; and they can advocate for increased attention and investment in education in crisis settings at regional and global forums, while forging partnerships with governments, NGOs, and international agencies to amplify impact and reach. Many examples can be drawn, throughout the continent.

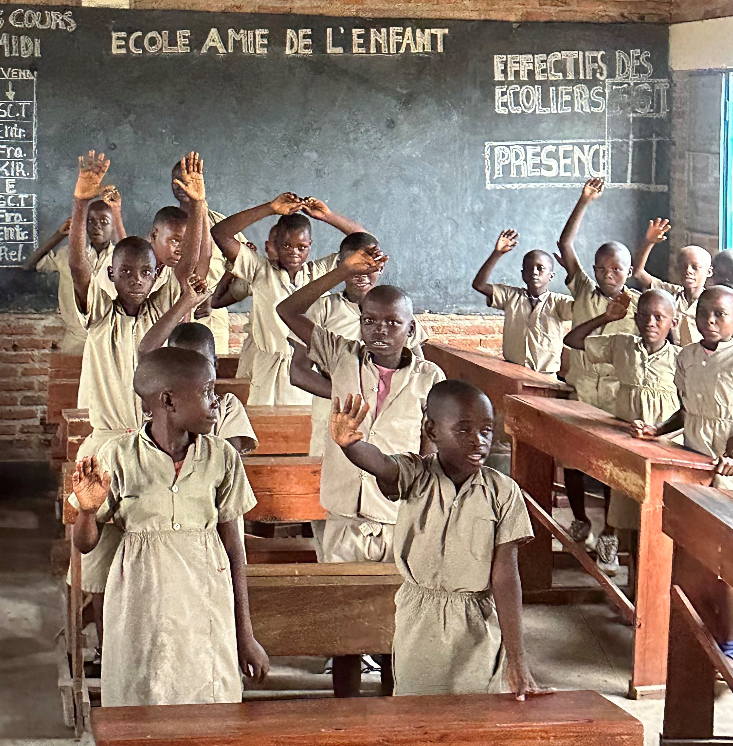

For example, on education delivery for girls and boys impacted by armed conflict, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has established the "Children, Not Soldiers" campaign in collaboration with the United Nations, advocating for the release and reintegration of child soldiers and prioritizing their education and rehabilitation.

In Somalia, GPE has partnered with the government to support the rebuilding of its education system, providing funding for teacher training, school construction and curriculum development in conflict-affected regions.

On displaced children, civil society organizations play a crucial role in engaging communities, advocating for children's rights, and providing education services in hard-to-reach areas. They can work closely with communities to identify needs, mobilize resources and implement education programs tailored to local contexts.

In South Sudan, for instance, organizations like Save the Children and UNICEF have established temporary learning spaces and community-based education programs to reach children affected by conflict and displacement, ensuring continuity of learning in challenging environments.

The Education Cannot Wait (ECW) fund has supported countries like Nigeria in providing education for internally displaced children affected by the Boko Haram insurgency, focusing on building inclusive and resilient education systems. Likewise, in the Western Sahara refugee camp of Tindouf (Algeria) UNICEF, WFP, UNHCR and NGOs are supporting children’s education.

On climate change-induced disasters, following the devastating impact of Cyclone Idai in 2019, Mozambique has been working with international partners to rebuild and strengthen its education infrastructure. The intervention includes constructing cyclone-resistant schools and developing early warning systems to protect schools from future disasters. Kenya is implementing a climate change curriculum in primary and secondary schools to educate about climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies.

By leveraging the expertise, resources and collective efforts of African Union member states, donor organizations, civil society partners and multilateral organizations, it's possible to transform and accelerate the delivery of education for children impacted by crises in Africa, ensuring they have access to quality education and opportunities for a brighter future.

AU Member States can foster innovation in education delivery, such as leveraging technology for remote learning and establishing temporary learning spaces in refugee camps and disaster-affected areas; enhance the capacity of education systems to respond effectively to crises, including training teachers and education personnel in trauma-informed pedagogy and psychosocial support; and engage communities, including parents, local leaders and affected populations, in the design and implementation of education programs to ensure relevance and sustainability.

For instance, through Japanese funding, the International Institute of Capacity Building in Africa (UNESCO-IICBA) supports the African Union International Centre for Women and Girls Education (AU-CIEFFA) in two main projects. The first one aims at creating safe, supportive, and resilient learning environments to safeguard children’s right to education amid conflict and crises in the Sahel, Central and East Africa with a budget of US$1,155,000. The second relates to capacity-building of teachers to promote continuous and inclusive access to safe and quality education for girls in west Africa with a budget of US$3,260,000.

ECW: Approximately 98 million children are out-of-school across sub-Saharan Africa. In areas impacted by armed conflict, forced displacement, climate change and other protracted crises, girls are especially at risk of dropping out, being forced into child marriage, and being denied their human rights. Why must we redouble investments in girls’ education?

Professor Mohammed Belhocine: Redoubling investments in girls' education is imperative, especially in areas affected by armed conflict, displacement and climate crises, considering the Safe Schools Declaration. It is believed that girls in these contexts face heightened risks of dropping out, child marriage and human rights violations. This adds to the fact that even in “normal” times, less girls attend school than boys.

Against this backdrop, the African Union Commission established the African Union International Centre for Girls and Women (AU-CIEFFA), to coordinate the promotion of girls’ and women’s education in Africa, with a view of achieving their economic, social and cultural empowerment. The Centre works closely with AU Member States and government, civil society, and international partners to keep girls’ education as a priority concern. We all know that education is a driver for peace and stability. By ensuring that girls have access to safe and quality education, we can help prevent conflict, promote social cohesion and contribute to long-term peacebuilding efforts which, invariably, will promote gender equality and women's empowerment. It will protect girls from social abuses: child marriage, human trafficking, sexual abuse, child labour and so on. We must redouble investments in girls' education to implement the Safe School Declaration, which has been ratified by 35 AU member States and which reaffirms the commitment to protect education from attack during armed conflict. Redoubling investments in girls' education should include implementing measures outlined in the declaration to ensure safe learning environments for all children, especially girls, in crisis-affected areas. COVID-19 exacerbated those vulnerabilities.

ECW: There is a massive funding gap for education across Africa, particularly for girls and boys impacted by emergencies and protracted crises. Why should donors, the private sector and high-net-worth individuals invest in education in Africa through dedicated funds such as “Education Cannot Wait”?

Professor Mohammed Belhocine: Donors, the private sector and high-net-worth individuals are encouraged to invest in education in Africa, through efficiently dedicated funds, such as Education Cannot Wait.

One of the reasons here should be for long-term stability and peace. We all know that education plays a crucial role in fostering social cohesion, promoting peacebuilding and preventing conflict. By investing in education in Africa, donors can support initiatives that provide safe and inclusive learning environments, promote tolerance and understanding, and empower young people to actively participate in building peaceful and stable societies.

On the other hand, education is a key determinant for economic development. Education is a powerful catalyst for economic growth and poverty reduction. By investing in education, donors can help equip young Africans with the knowledge and skills they need to participate in the workforce, start businesses, and contribute to their communities' development. This, in turn, can have positive ripple effects on Africa's overall economic prosperity. Experts teach us that the mid-term return on investment in education is one of the highest.

In addition, education is closely intertwined with health outcomes. By investing in education, donors can support initiatives that provide children with essential health education, promote positive health behaviours, and contribute to better health outcomes for individuals and communities. Furthermore, education can also serve as a protective factor against issues such as child marriage, early pregnancy and other harmful practices.

Therefore, investing in education in Africa through dedicated funds such as Education Cannot Wait is not only a moral imperative, but also a strategic opportunity to build a better future for millions of children and youth, unlock the continent's potential, and contribute to global progress and prosperity.

ECW: As seen by droughts in the Sahel, flooding in Libya and East Africa, and other climate-induced disasters, climate change is a major threat to sustainable development across Africa. How can we better connect the dots between climate action and education action to build a more sustainable future for Africa?

Professor Mohammed Belhocine: Connecting climate and education actions is better done within existing African Union’s Frameworks, aligned with Agenda 2063, for a more sustainable future in Africa.

One of the steps to take is to implement initiatives to make schools more environmentally sustainable, such as smart water management, incorporating renewable energy sources, promoting waste reduction and recycling, as well as integrating environmental themes into school activities and infrastructure development. This can also be done by engaging local communities in climate education and action through outreach programs, community-based projects, and partnerships with grassroots organizations, fostering a sense of ownership and collective responsibility for climate change resilience and environmental stewardship.

These actions cannot go without providing training and support to educators, policymakers and community leaders on climate change mitigation, adaptation and resilience-building strategies, empowering them to lead effective initiatives at the local, regional and national levels. This can also lead to investment in research and innovation to develop context-specific solutions to climate-related challenges in education, leveraging indigenous knowledge and technology to build resilience and promote sustainable development.

Lastly here is the need to foster collaboration between education and environmental ministries, as well as other relevant sectors such as agriculture, energy and water resources, to develop holistic approaches in addressing climate change through education and policy integration. The need to raise awareness about the interconnectedness of climate change and education, calls for increased funding, policy support and international cooperation to address both issues effectively and equitably.

ECW: We all know that ‘leaders are readers’ and that reading skills are key to every child's education. What are three books that have most influenced you personally and/or professionally, and why would you recommend them to others?

Professor Mohammed Belhocine: The more you read, the more you learn. As one famous singer put it: “I am a beginner with whitening hair.”

It’s difficult to select only three books, as all of them would influence you in one way or another. Screening through my recent and ancient readings, and trying to link your question to our discussion, I would single out three important titles: The first one is the monumental work of Cheikh Anta Diop, Pre-colonial black Africa (1960), which, when published, constituted a major epistemological break with hitherto received ideas on African historical sociology. It is a must for whoever wants to better understand the anthropological, social, cultural, scientific and economic foundations of African societies. The second relates to the famous best seller Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (2012) by Yuval Noah Harari. Combining natural and social sciences, the author offers, in a simple and pleasant style, an overview of the history of mankind from the Stone Age to the 21st century. This book was followed by another one from the same author, questioning the future of humankind: 21 lessons for the 21st century in an era of ever evolving technologies.

Many other titles come into my mind. These include, for instance, the works of Joseph Ki Zerbo on African history, culture and education, and many novels from African and non-African novelists, but let me stop here.

As we enter the digital era, I cannot but encourage our youth to read books, because reading a book helps consolidate our knowledge, our memory and our critical thinking, and ultimately, forge our character.